What is Cognitive Bias?

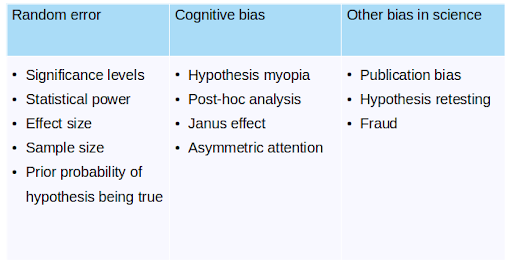

Our brain has evolved to process tremendous amounts of complex data and make coherent decisions based on them. But ultimately, our brain has evolved for survival in the wild and not in the lab. While our scientific education has trained us to dissect problems rationally, our brains are unconsciously always looking for shortcuts to help us make decisions more efficiently. Unconscious mental shortcuts, also called heuristics, sometimes lead to irrational judgements. This phenomenon is called cognitive bias. Cognitive bias can also lead to systematic deviations in the way we perceive and analyze data, which can lead to false findings. This is why cognitive bias is a researcher’s worst enemy.

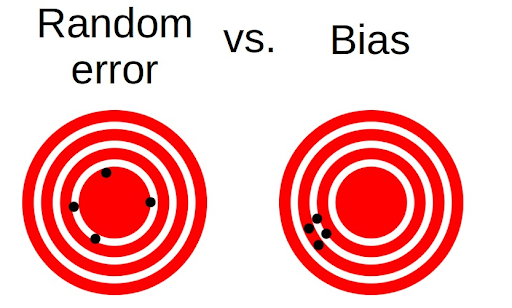

Figure: Systematic patterns in false findings are an indication of bias.

Most of our cognitive bias stems from desirability. Our brain is wired to look for confirmation of that which we believe or expect to be true. Unfortunately, this natural tendency goes directly against the fundamentals of science. According to science philosopher Karl Popper, confirmation vs. falsification is exactly what differentiates science from pseudo-science.

Cognitive bias is likely to occur when the stakes are highest. Pharmaceutical executives are keen to get new drugs to the market as jobs might be at stake and investments are high. Contrary to what some may think, academia is not significantly more bias-proof. Career and funding pressure makes researchers just as eager to report positive findings. We will therefore discuss four typical forms of cognitive bias in research and how they can be mitigated:

Cognitive Bias #1: Hypothesis myopia

Some data looks more plausible than others, doesn’t it? If the most plausible data supports my hypothesis, that should prove it as true, right? Wrong. Collecting evidence in support of your theory, while ignoring information that falsifies it, is a common form of bias. Take this RCT study claiming a positive effect of prayer in health outcomes. While only one of the multiple score methods turned out significant, the authors presented the most significant scoring method in support of their hypothesis.

Mitigation:

Strictly follow the scientific method. Define a null-hypothesis and alternative hypothesis and only reject the null-hypothesis if the data does not plausibly explain the null-hypothesis.

Cognitive Bias #2: Tendency to revise your hypothesis post-hoc

After collecting your data, you may find that you’ve missed your primary end-point by only a fraction. Revising our end-points ever-so-slightly wouldn’t hurt anyone, right? Wrong! Changing your hypothesis post-hoc is actually one of the bigger sins in science, as this allows researchers to go on “data dredging” or “fishing” expeditions to prove whatever they want. Any large enough dataset will contain relations that look statistically significant by chance.

Mitigation:

Define and publicly declare your hypotheses before data collection. This will restrict you from the temptation to change the hypothesis after the fact.

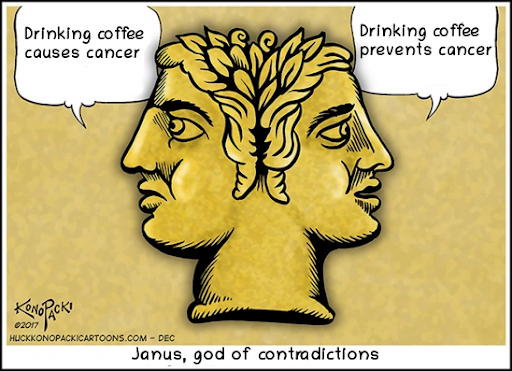

Cognitive Bias #3: Assuming that the analysis method with the most desired outcome is the correct one

Ah, we almost made our end point. We must have made a methodological error somewhere. Shall we revise our methods slightly? Manipulating the methodology to support your hypothesis is a common issue. For example, a team of German researchers found that people on a low-carb diet lost weight 10 percent faster if they ate a chocolate bar every day. Later they made it public that this was actually an attempt to show ‘p-hacking.’ John Ioannidis, MD, Professor of Medicine and Statistics at Stanford University, showed how you can analyze a dataset in a million different ways, something he calls the ‘Janus phenomenon.’ Your analysis method—in terms of framing, adjustments and inclusion criteria—can impact the outcome of your results.

Mitigation:

Have your methods vetted by peers before you start. Then, strictly define and follow your protocol.

Adapted from: uft.org

Cognitive Bias #4: Asymmetric attention

“That outlier can’t be true. See, if we remove it, our results become significant…” It is not uncommon for your study to collect outliers that distort the desired picture. It is very tempting to scrutinize these outliers more than you would the results around them. Unconsciously, you are looking for ways to exclude the undesirable results from your dataset.

Mitigation:

The most rigorous way to mitigate this issue is to ask someone to blindly analyze the data who has no vested interest in the outcome.

Source: Nature

What can be done?

It is very likely that clinical research, like any other research field, is riddled with cognitive bias. Researchers are human beings and hence are affected by cognitive bias. Bias is exacerbated by a lack of training in statistics and methodology. Researchers often use statistical methods they are familiar with or which are easily available to them. This can lead to the failure to eliminate the bias from their data. Luckily, statistics and methodology provide us with a strong toolbox to counter our natural tendencies. The better our awareness of our biases, the better we can put procedures in place to mitigate these, and the better we will become as researchers.

Castor EDC is committed to improving research practices and data quality and we are writing a series of articles to understand and improve the medical research process. In the previous article, we discussed five factors that contribute to issues of replication in medical research, leading to the debate about whether or not medical research is facing a “replication crisis.” Don’t want to miss out on this series? Subscribe below.